Protecting and promoting the mental health of babies and young children is part of ensuring that children are happy and healthy now and have the foundations to thrive in the future. In this blog, we turn to Sally Hogg, Senior Policy Fellow at the Centre for Research on Play, Education, Development and Learning (PEDAL) at the University of Cambridge, who gives us five things we need to know about mental health in the early years.

Last month, working with UNICEF UK, we published a new toolkit to help partners from different services and professions to develop a deeper, shared understanding of mental health in infancy and early childhood, and the factors that influence it. You can find the toolkit here.

Image: Unicef UK

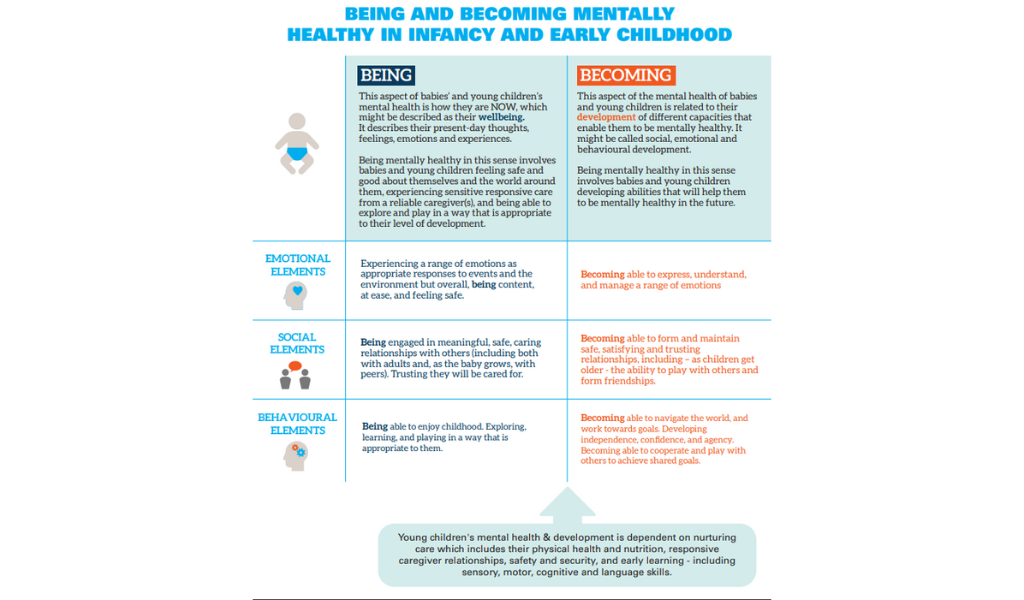

Being mentally healthy is a positive state that enables us to enjoy life and deal with challenges.

Often people understand the term “mental health” in ways that make it more difficult to apply it to babies and young children. For example, mental health is often mistaken to mean mental health problems or diagnosable disorders. This framing makes it difficult to understand babies’ and young children’s mental health because generally, it is not possible or appropriate to diagnose the mental health conditions that occur in older children and adults in the same way in early childhood.

Mental health is also often thought of as something located in an individual – as an innate strength or deficit. This framing makes it difficult to understand babies’ and young children’s mental health, which is usually shaped by their environment and relationships.

The UNICEF toolkit describes what it means to be mentally health in early childhood. We hope this framework can help people to understand mental health in this life stage.

Image: Unicef UK

All children, including babies and young children, have a right to be healthy, which is set out in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. As early years practitioners, you can help ensure babies and young children are mentally healthy now, free from prolonged stress and distress, and having a good life, from the start.

The earliest years of life also provide the foundation for later development. Early years practitioners can support babies and young children to develop capacities, like emotional regulation, which support them to be mentally healthy throughout life.

Our Early Years Library helps early years practitioners support young children’s development. It provides a comprehensive set of low-burden strategies and activities to support social and emotional development, which can be integrated into everyday practice.

Nurturing relationships, particularly the relationship between the child and their parents or primary caregiver(s), are the most significant protective factor for the mental health of babies and young children.

Sensitive, responsive, consistent relationships with adults support wellbeing and development in several ways: these relationships help children to learn how to experience, manage and understand their emotions, and feel safe and secure to explore the world around them. Early relationships provide a template for children’s expectations in later relationships. Nurturing relationships also help young children to develop their sense of self and support the development of language and cognitive functions. Caregivers can also support early wellbeing and development through engaging young children in stimulating activities such as play and book sharing.

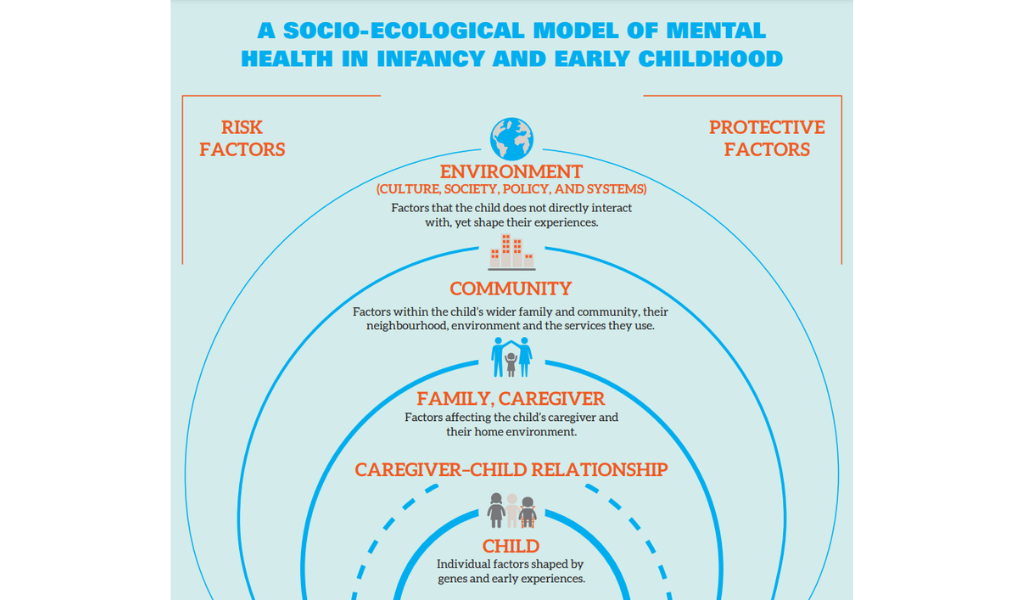

Mental health occurs as a result of a complex interplay between many individual and environmental factors, such as a baby or young child’s own characteristics, the quality of their relationships, and the communities and environments and society they live in.

The socio-ecological model in the UNICEF toolkit describes the different factors that each shape mental health from pregnancy through childhood.

Image: Unicef UK

All babies and young children struggle to manage their emotions and exhibit behaviours that challenge at times. For most children this is a normal part of development or a transient problem. However, some young children may show emotional or behavioural problems that are more extreme, persistent across different contexts, cause more significant distress and/or stop children being able to play, interact and learn.

Significant and persistent issues should prompt professionals to be curious about what is happening for a child. Problems in regulation, behaviour and emotion may be due to factors at any of the levels described in the socio-ecological model. The same external behaviours might indicate different underlying factors in different children. While some problems may be the result of a child’s biology or a developmental condition, others might be an adaptive response to situational factors and the child’s experiences, such as exposure to extreme stress at home. Regular contact with children, and a holistic understanding of their development, relationships and home environment are important to addressing any emotional or behavioural problems they may display.

Being able to play is part of being mentally healthy in early childhood. Mentally healthy children are more likely to be playful, and to feel confident and safe to play.

Research shows us that both free-play and guided-play in the early years can support many elements of children’s mental health. For example, playful interactions can support the formation and maintenance of relationships with adults, and friendships with peers, which are of crucial importance for health development.

About the author

Sally is Senior Policy Fellow at the Centre for Research on Play, Education, Development and Learning (PEDAL) at the University of Cambridge. PEDAL is the Centre for Research on Play in Education, Development and Learning to help mobilise knowledge to help to improve children’s lives and life chances.

Sally is a specialist in early childhood, with a varied career including leadership roles in charities, national and local governments. Before joining PEDAL, Sally was Deputy Chief Executive at the Parent-Infant Foundation where she led work to raise awareness of the importance of the earliest years, and to drive change at a local and national level.

She has also held other influential roles in the early childhood sector including Strategic Lead at the Maternal Mental Health Alliance and Development Manager for Children Under One at the NSPCC, where she developed and implemented research-led interventions.