Engaging in autonomous play can boost cognitive abilities and even lay the foundation for lifelong learning for young children. In this blog, Tricia Mohamed explores how play can enhance children’s Lantern Brain.

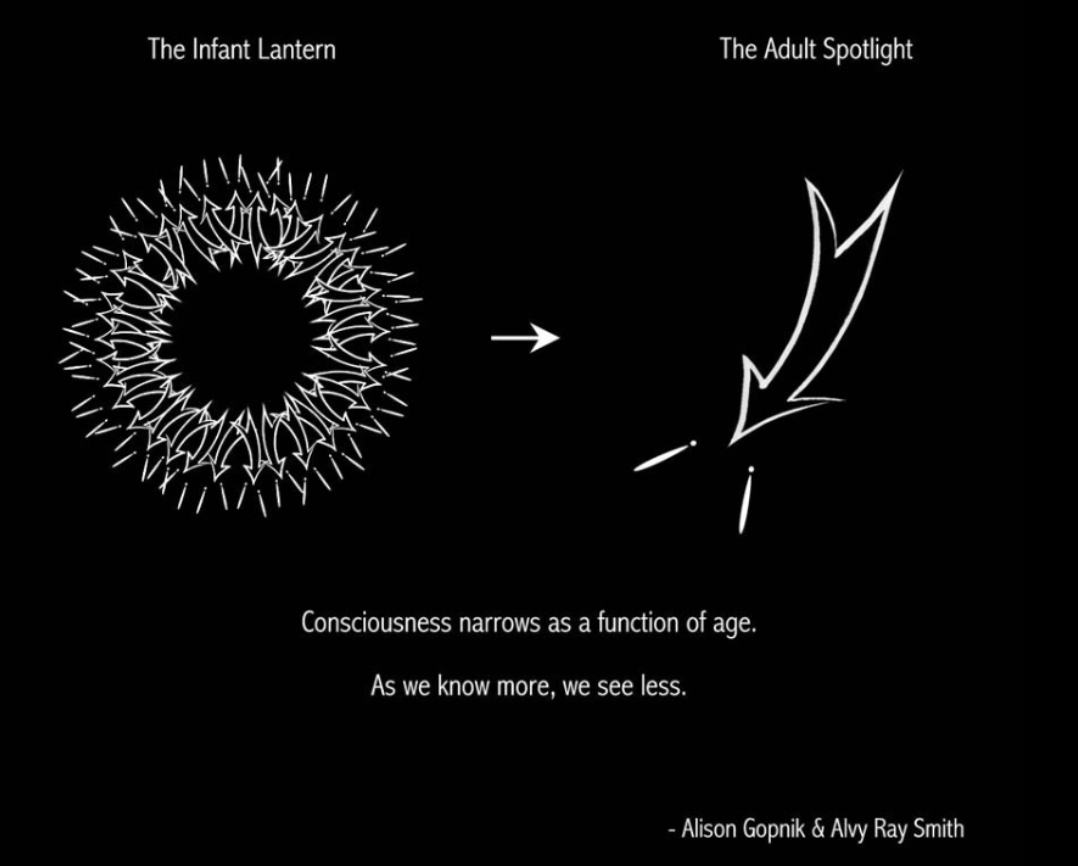

The brains of adults and children function quite differently. For example, consider the simple task of going to the shop to buy a pint of milk. As an adult, you might be so focused on this goal that you hardly notice anything else. In this case, your brain is operating in “spotlight mode.”

Now, imagine going to the shop with a young child. Upon leaving the house, they might notice a vibrant pink rose in the garden, a person walking their dog, an aeroplane in the sky, someone riding a bike, and even the sound of a cat hiding behind a bush. When they arrive at the shop, they will likely be captivated by the bright colours and various products at their eye level, prompting them to ask you to buy something for them.

In this scenario, the child’s brain is in “lantern mode,” observing and noticing everything around them.

The reason for these differences is that adult and child brains have evolved for distinct purposes. The adult brain has developed to be more efficient for decision-making, while the child’s brain is designed for exploration and learning, which is often facilitated through play.

A baby with a rattle has no preconceived notions about what a rattle is or what it does. Initially, the baby will observe the rattle using its senses. It might hypothesise, for example, “Is it tasty?” The baby may place the rattle in its mouth to test this hypothesis. Based on the outcome, the baby will either choose to test the theory again or develop a new hypothesis to explore. Repeatedly testing these hypotheses strengthens neural connections and facilitates new learning.

In contrast, an adult approaches the rattle with preconceptions shaped by past experiences and will immediately shake it. The adult’s brain is focused and decisive.

Meanwhile, the child’s brain, which operates like a lantern, is more exploratory and inquisitive. Play serves as the child’s method of research.

As an educator, parent, or caregiver, you play a crucial role in nurturing a child’s Lantern Brain. Here are some straightforward ways to support brain development through play:

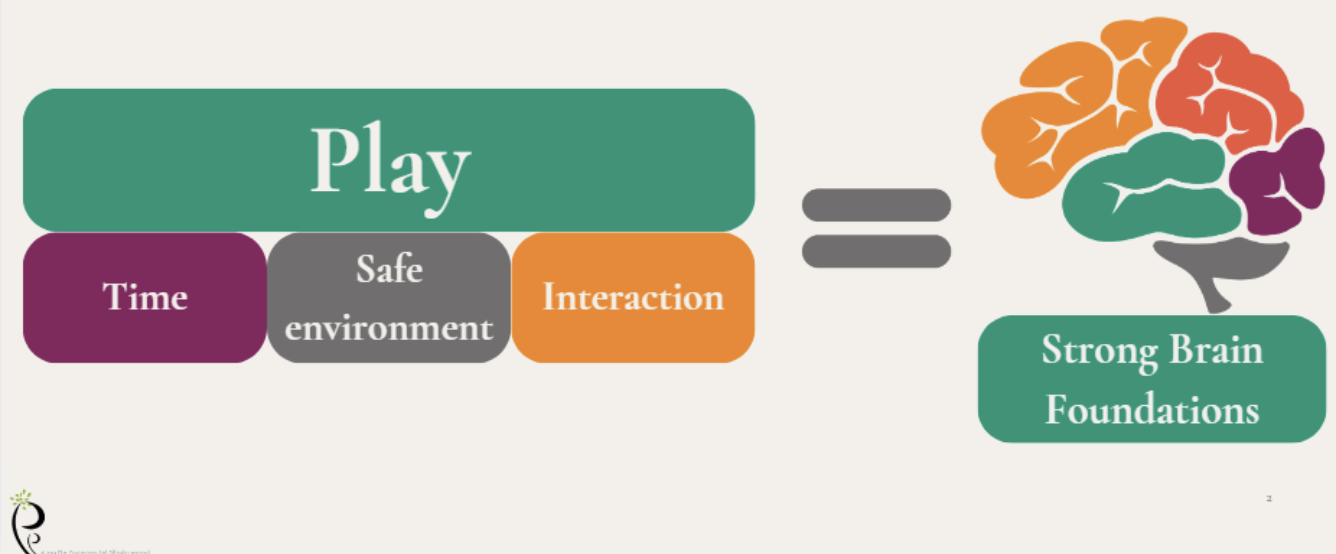

1. Make Time for Play:

Set aside regular, uninterrupted time for play. This may involve using mealtimes or naptimes as natural breaks. Allowing the child to engage in deep play helps them explore their ideas repeatedly. The more time a child has to test their hypotheses, the stronger their neural connections will become, leading to deeper learning.

2. Provide Safe Environments:

Whether indoors or outdoors, an emotionally safe environment is one where children feel their ideas are valued. A safe space should have a predictable routine and accessible resources. Creating a workshop-like environment is ideal for children’s Lantern Brains, enabling them to explore the possibilities and limitations of resources repeatedly, which strengthens neural connections. Additionally, using neutral decor and natural lighting can help children focus more easily on their learning.

3. Be Present and Engaged During Interactions:

Whenever possible, play alongside the child. Show genuine interest in their activities, ask open-ended questions, and provide encouragement. Your active involvement in play fosters bonding and facilitates deeper learning. Crouch down to meet children at their eye level, engage in loving interactions, and if you feel the urge to dominate the play with your adult spotlight brain, take a moment to ask yourself:

– Is it hurting the child?

– Is it hurting other children?

– Is it breaking resources?

If the answer to all these questions is no, take a breath and observe as the child’s Lantern Brain builds strong foundations for learning that will last a lifetime.

Watch Tricia’s webinar on this subject, subscribe to Kinderly Learn today for less than £2 per week with an annual subscription!)

References

Fisher, A. V., Godwin, K. E., & Seltman, H. (2014). Visual Environment, Attention Allocation, and Learning in Young Children: When Too Much of a Good Thing May Be Bad.

Gopnik, A. (2009). The philosophical baby : what children’s minds tell us about truth, love & the meaning of life / Alison Gopnik. The Bodley Head.

Tricia Mohamed is a UK-qualified teacher with over 25 years of experience working in education both in London and internationally. Having spent decades in diverse educational settings, Tricia brings a wealth of practical insight and a deep understanding of the challenges and opportunities educators face today. As the founder of Play Practitioners, a bespoke consultancy and training provider, Tricia is committed to helping educators and parents maximise children’s learning potential through tailored solutions.

Play Practitioners is grounded in the latest research on play and neuroscience, ensuring that the services offered are not only personalised but also evidence- based. With a keen awareness of the importance of both local and global perspectives, Tricia adopts a “glocal” approach, recognising the significance of each child’s immediate setting while drawing on global research and best practices.