If you work in the Early Years, you will be supporting neurodivergent children (diagnosed or not), many of whom will have sensory needs different to those of their neurotypical peers. In this post, Zoë Austin will be focusing on supporting autistic and ADHD children:

1) because she is autistic and ADHD and part of her profile includes interesting sensory processing, so can speak from first-hand experience;

2) because she has a great deal of experience working with this community of learners, across the lifetime, and;

3) because autistic and ADHD folks are very likely to experience heightened sensory delights and struggles in their daily lives. These children’s experiences deserve to be respected and supported to the best of our ability as practitioners. Here are some thoughts on how this might be achieved, and what we need to consider to be in the right frame of mind to do so.

It is now understood that there are more than what we used to believe were the five senses (sight, hearing, smell, touch and taste). Search for just how many there are, and you will get answers from 7 to 22, but here I will be focusing on 8 of them: the five above, plus proprioception (the sense of where one’s head is in relation to space and objects in our environment); interoception (sense of what is happening within one’s own body) and mechanoreception (which concerns vestibular feedback centred around the vestibule in the ear – responsible for our sense of balance).

Simply put, our brains are built and develop in such a way that we often take in extra amounts (or, less frequently, very limited amounts) of sensory data when compared to neurotypical brains. In my recent Kinderly webinar on supporting sensory needs in Early Years, I talked about a process called ‘synapse pruning’, which neurotypical brains begin to undertake around age 4-5, but which is limited in autistic brains. This means that our autistic brains retain more “brain wiring”. If we have more synaptic receptacles in our brains, we are, naturally, going to absorb more data.

That said, children in the early years are too young for synapse pruning to have begun, so there is something about the structure of our brains, from even before we are born, which makes us more sensory-sensitive. This needs to be taken into account by any professionals seeking to support us in any way.

It is at this point that I attempt to hammer home to you, dear reader, one of the key messages of this post:

Please, please, please do NOT assume that you understand that sensory experience of a child. And please trust them when they communicate their sensory experiences to you.

By that, I mean that, if you are a neurotypical practitioner, and you don’t believe the lights are too bright in your setting/a noise is upsetting/a food tastes too strong/a scent makes you gag etc., the opposite may be different for a neurodivergent child in your care. You have NO way of knowing what is happening in their brain, so please do not diminish, dismiss, undermine, or disbelieve them when they tell you (by whatever communication means they have at their disposal) that they are struggling. Far too often, I have heard mainstream primary school staff do exactly that thing, saying things like, ‘He just needs to toughen up.’ ‘Well, she needs to get used to it here.’ ‘They’re just coddled at home and allowed to get their own way all the time’ (when, in fact, their parents are doing a great job of meeting their autistic child’s needs at home).

Imagine being bombarded by sensory information for hours at a time. This can be a frightening and, frankly, exhausting experience. A child may deal with this by hiding, not wishing to socialise/communicate with other children or adults, or, at worst, they may be pushed to the point of meltdown (NB: meltdowns are NOT the same as temper tantrums – a topic for another post!) or shutdown. No education/care provision should ever bring about such experiences for any child.

If we are dismissive of children’s experiences (‘It’s not too bright, don’t be silly’), they eventually adopt the understanding that they are the problem. They know they are struggling, but if they are, frankly, gaslighted into believing that their own experience is untrue, imagine the long-term implications for their mental health! Autistic people are 9 times more likely to die of suicide than non-autsitic people, with autistic women 13 times more likely to die of suicide than their non-autistic peers. 80% of autistic adults and 70% of autistic children experience mental illness (1). Mental health issues are not a part of being autistic. Autism doesn’t cause mental ill health: it is the life experiences of the autistic person which brings this about. As Early Years practitioners, we know what an important developmental period of a child’s life they spend in our key stage/age group, so it is our responsibility to respectfully support our neurodivergent children to the best of our abilities; to help them build healthy, strong foundations within themselves from which to launch, with high self-esteem, into the world, safe in the knowledge that they matter just as much as everyone else, and protected (as much as possible) from the distresses of sensory overload.

Another potentially damaging effect of a child being subject to sensory overload is that they will experience fear and, potentially, trauma. Fear triggers the amygdala’s “fight or flight” response, and long-term exposure to this can impact brain development. Sadly, I do not have the space to expand upon this in this post, but there is a wealth of information available online for the trauma-informed practitioner to explore.

It is not all bad news for the sensory-sensitive child. Along with sensory challenges, comes the flip-side of the coin: sensory delights. Absorbing more sensory data means that we neurodivergent folks can also experience sensory pleasure on a much deeper level than neurotypical people. If we enjoy a sensation, we want to repeat it, make it last as long as possible. Have you noticed signs of sensory-seeking in children you support? Do they particularly enjoy playing in water or sand; smelling or stroking particular items; do they seek you out for the proprioceptive joy of a big, squeezy hug? When I was at nursery, I used to escape the uncomfortable noise of the main room by hiding in the cloakroom, door closed behind me, and lying on the cool stone floor. To this day, I can remember the profound peace and happiness I experienced every time I did this.

Children may discover and seek out sensory delights for themselves, but we can also consider what they might enjoy (or find difficult) beforehand: we can mute lighting in our rooms (strip lights = evil!), provide quiet spaces, have a ‘cuddle corner’ full of soft toys, blankets and cushions.

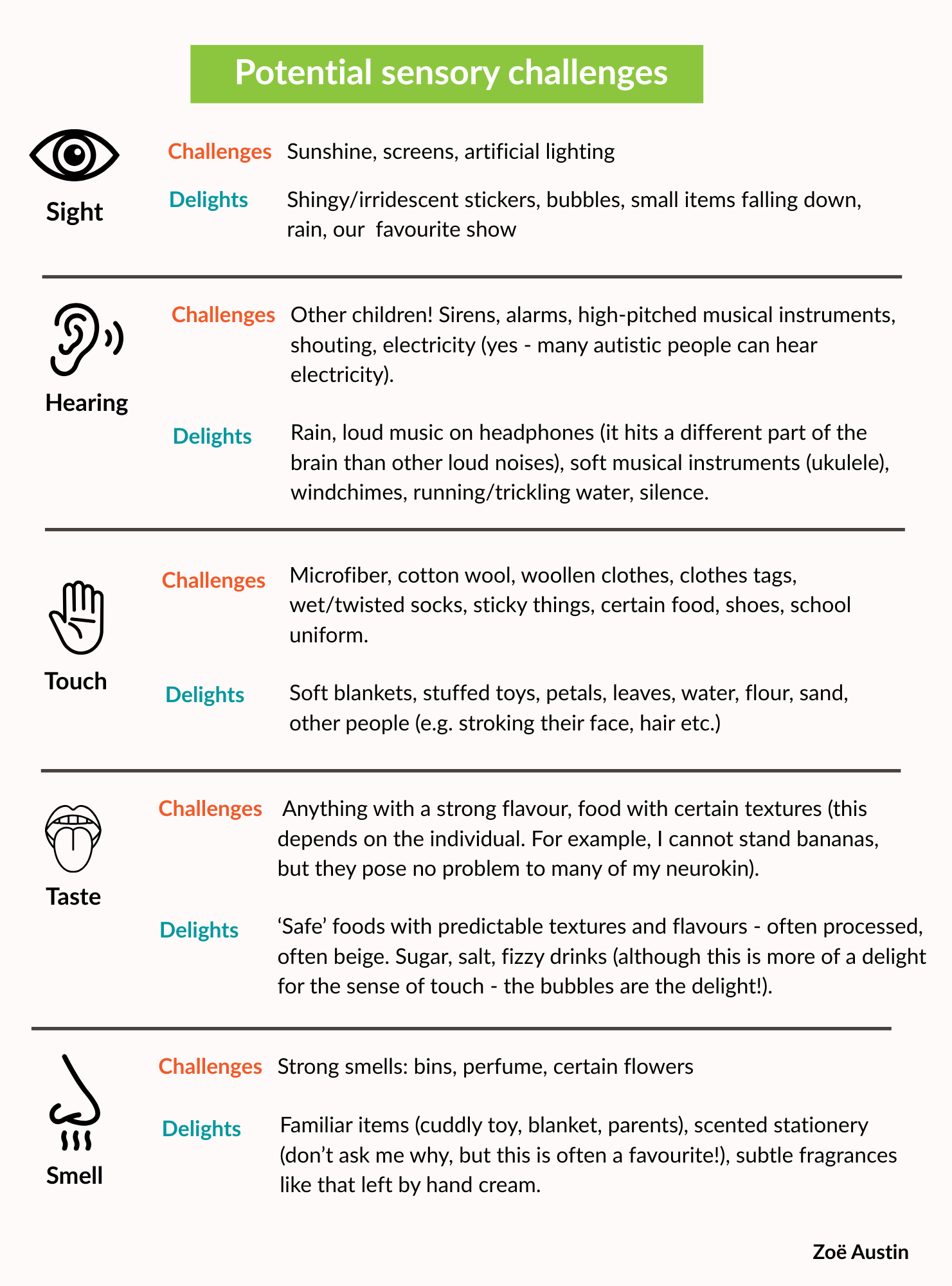

Here is a (by no means exhaustive) list of other potential sensory challenges and delights experienced by autistic/ADHD children. They may or may not be relevant to children in your setting:

Interoception

Autistic children may experience hyper- (increased) or hypo- (decreased) interoception: they may be keenly aware of what is going on in their bodies (and, therefore, something like a stomach ache which would not perturb a neurotypical child might be extremely painful to their autistic friend) or, by contrast, they may be unaware of feeling thirst, hunger, pain, illness, heat or cold. It is the responsibility of the adults around them to monitor these children closely as they may, for example, have received an injury but be unaware of it.

Proprioception

The challenges of hypo-proprioception (it doesn’t tend to come in the ‘hyper-’ variety, as far as I am aware) can result in what would be labeled “clumsiness”. I have real issues with proprioception: I cannot really sense where I am in relation to (often large) objects around me, so I am constantly dropping and walking into things. There will be ways to risk assess for a child with similar experiences, and adapt our settings accordingly.

Mechanoreception

Difficulties with vestibular balance can also impact a person’s movement and mobility. It also effects posture – many of we autistics have “poor” posture which can effect, for example, lung health (in the case of the slouching autist).

I invite you to view your setting with new eyes: those of a child who experiences the world in technicolour, surround-sound, stars glistening to the moon and back. Any adaptations you make for them will also be of benefit to their neurotypical peers (dimmed lights are good for all children’s eyesight. All children love soft blankets etc.). Make the place where they spend their daytimes a safe, comfortable zone where they feel properly seen and cared for. We all know that the best learning occurs when children’s needs of well-being are met. Now you can consider and meet the sensory needs of all your children, whatever those needs may be. And please, don’t just meet them: advocate for them.

About the author

Zoë Austin is a freelance neurodivergent educator living in Cambridgeshire and working across East Anglia. She divides her time between providing group and individual music sessions, 1:1 tutoring for autistic/ADHD school-age children, mentoring autsitic/ADHD university students, and writing/presenting on the subjects of neurodiversity, child development, and music-making. Part of the Pen Green Schema Group, she contributed to the book Schemas in the Early Years (Routledge, 2022), and presented on ‘Schema theory and children’s emerging musicality’ at EECERA, 2023. Zoë uses her past experiences as a (Pen Green-trained) classroom teacher, Music Therapist and working in children’s social services to inform her position as a holistic practitioner, creating learning opportunities to meet the needs of the individual child as a whole person.