Have you ever observed a child engaging in the same behaviour repeatedly and found yourself feeling perplexed or even frustrated by their persistence? It can be pretty puzzling when a toddler repeatedly throws their food off the table or when they seem utterly fascinated by the simple act of turning a tap on and off, exploring the flow of water with unyielding curiosity. You might also find yourself reading the same storybook over and over as your little one eagerly requests yet another reading of their favourite tale. This cycle of repetition—often seen as mere play or annoyance—is a vital part of their learning process. It’s a reflection of their means of grasping and exploring specific concepts, termed as “schemas.”

Drawing from the foundational work of Piaget, Chris Athey deepened the understanding of schemas, describing them as “a pattern of repeatable behaviour into which experiences are assimilated and that are gradually co-ordinated. Co-ordinations lead to higher-level and more powerful schemas” (Athey, 2007: 50). In essence, when you witness a child engaged in repeated behaviours, know that they are on a quest to understand the intricate world around them. They are not merely playing; they are actively exploring, testing boundaries, and formulating hypotheses about the abstract concepts that govern their reality. Through their repetition, they are building foundational knowledge and insights that will support their cognitive development as they make sense of their experiences.

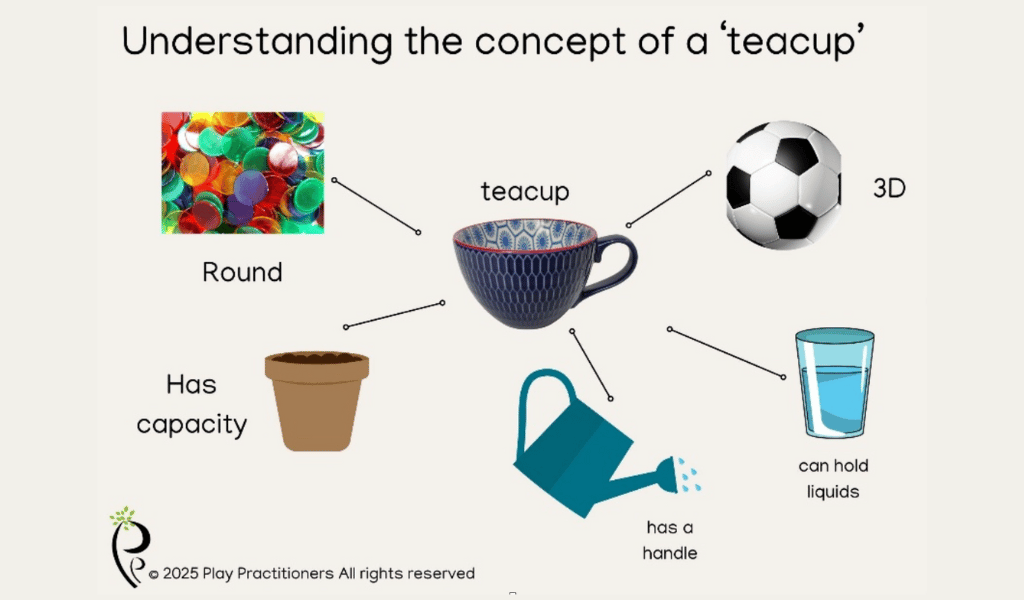

Let’s explore the idea of a cup. When I mention “cup,” many of you may picture something round. Now, imagine a counter – it’s round, but it’s flat, so that’s not a cup. Now imagine something that is round and three-dimensional, but that’s likely to be a ball, which doesn’t hold anything inside, so it’s not a cup. Next, consider the flowerpot: it’s round, three-dimensional, and can hold items; however, it still isn’t a cup because it can’t carry liquids. Now, imagine a glass, a round, three-dimensional object that can hold liquids, but it’s still not a cup because it’s made of glass. A child’s grasp of what a cup is grows through the development of schemas and the language we associate with them. This is where educators come into play, providing language to label the concept a “teacup” or “coffee cup.” As children become more familiar with the term “cup,” they can apply it in various contexts, for instance, when referring to cups as a measure in cooking or when referring to cupcakes.

Every time a child interacts with a concept, they are reinforcing neural connections, building an entire network of complex pathways. If we rush this process, those connections may remain weak and eventually fade away. Repetition is key, allowing neurons to fire together and ultimately wire together (Shatz, 1992).

Transporting Schema – Children love carrying objects from one place to another.

Concepts: object permanence, weight, capacity, planning, location.

Positioning Schema – Children enjoy arranging objects in a specific order or pattern.

Concepts: spatial, patterns, mathematical, problem-solving.

Rotation Schema – Children love spinning, twirling, and turning things.

Concepts: centrifugal force, momentum, balance, clockwise/anticlockwise, engineering, symmetry, rotational angles.

Trajectory Schema – Children enjoy throwing, dropping, or running in straight lines.

Concepts: speed, force, gravity, direction, distance, angles, control.

Enveloping Schema – Children wrap objects or themselves.

Concepts: object permanence, spatial awareness, the difference between inside/outside/around, size, shape.

Enclosure Schema – Kids enjoy surrounding themselves or objects within spaces.

Concepts: boundaries, inside/outside, capacity, shape, size, area.

Connecting Schema – Kids like joining things together.

Concepts: problem-solving, spatial awareness, cause and effect, stability, balance.

Transforming Schema – Kids experiment with change, such as mixing substances.

Concepts: cause and effect, absorption, dissolve or separate, reversible or irreversible.

Orientation Schema – Kids explore different perspectives by turning upside down or looking at things from various angles.

Concepts: spatial awareness, perspective, angles, symmetry, inversion, rotation.

This process occurs most effectively when children are given the freedom to lead their play. At the same time, educators facilitate that journey by modelling language and providing ample time in an environment rich with open-ended opportunities.

Athey, C. (2007). Towards a constructivist pedagogy. In Towards a constructivist pedagogy (2 ed., pp. 37-58). SAGE Publications Ltd, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446279618

Shatz, C. J. (1992). The Developing Brain. Scientific American, 267(3), 60–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24939213

Arnold, C., & Mairs, K. (2013). Young children learning through schemas : deepening the dialogue about learning in the home and in the nursery / Katey Mairs and the Pen Green Team ; edited by Cath Arnold. Routledge.

Featherstone, S., & Louis, S. (2008). Again! again! : understanding schemas in young children / Stella Louis … [et al.] ; edited and with additional material by Sally Featherstone. A&C Black.

Nutbrown, C. (2006). Threads of thinking : young children learning and the role of early education / Cathy Nutbrown (3rd ed.). Sage.

About the author

Tricia Mohamed is a UK-qualified teacher with over 25 years of experience working in education both in London and internationally. Having spent decades in diverse educational settings, Tricia brings a wealth of practical insight and a deep understanding of the challenges and opportunities educators face today. As the founder of Play Practitioners, a bespoke consultancy and training provider, Tricia is committed to helping educators and parents maximise children’s learning potential through tailored solutions.

Play Practitioners is grounded in the latest research on play and neuroscience, ensuring that the services offered are not only personalised but also evidence- based. With a keen awareness of the importance of both local and global perspectives, Tricia adopts a “glocal” approach, recognising the significance of each child’s immediate setting while drawing on global research and best practices.