In 2008 the first Statutory Framework for the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) was introduced alongside a comprehensive pack of non-statutory ‘practice guidance’ which included the first version of ‘Development Matters’. The EYFS was extensively revised and slimmed down in 2012. A fully revised and updated ‘Development Matters’ was also published (Early Education, 2012) to accompany to new EYFS. In 2021 the EYFS was further revised with significant changes to the Learning and Development Requirements. A repurposed Development Matters was commissioned by the DfE as curriculum guidance to support the changes.

Visit our EYFS Hub with all the resources you need to stay updated with the revised EYFS and what it means for your practice.

In 2008 the first Statutory Framework for the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) was introduced alongside a comprehensive pack of non-statutory ‘practice guidance’ which included the first version of ‘Development Matters’. The EYFS was extensively revised and slimmed down in 2012. A revised and updated ‘Development Matters’ was also published (Early Education, 2012).

With the launch of the EYFS 2008 the early years community was introduced to a new concept, the ‘learning journey’. Practitioners were encouraged to celebrate a child’s experiences in their Early Years setting by recording each child’s journey: including observations; assessments; planning ideas; evidence of progress; and contributions from the child and their parents, then compile this information into a comprehensive file known as a learning journal. The journal would belong to the child and move with them as they transitioned, for example, between rooms in a setting or to a new setting or school, and could be added to by multiple settings, where care was shared.

The concept was a sound one and eagerly embraced, with practitioners producing beautiful folders that became a source of pride. Photos were carefully cut out and glued into the journals alongside copious post-it notes. Soon there were templates to print out, stickers to highlight areas of learning and ‘footsteps’ stampers to identify ‘next steps’. Development Matters statements were highlighted, trackers colour coded and ticked, reports written. Before they knew it, practitioners were buried in paperwork. Learning journals had stopped being a joyful celebration of children’s journeys and become a chore to be dreaded and endured.

The Tickell Review (DfE, 2011) acknowledged the concerns of the Early Years community around the issue of burdensome paperwork and recommended that this be addressed in the revised 2012 EYFS. This continues to be reiterated in the current EYFS.

2.2 Assessment should not entail prolonged breaks from interaction with children, nor require excessive paperwork. Paperwork should be limited to that which is absolutely necessary to promote children’s successful learning and development. (DfE, 2021)

There is currently no requirement in the EYFS to physically record any assessment data except the 2y-progress check (EYFS 2.4) and the Early Years Foundation Stage Profile (EYFSP) at the end of the reception year. It is up to practitioners to use their judgement to decide what to record and how.

2.1 It involves practitioners knowing children’s level of achievement and interests, and then shaping teaching and learning experiences for each child reflecting that knowledge.

2.2 Practitioners should draw on their knowledge of the child and their own professional judgement and should not be required to prove this through collection of physical evidence (DfE, 2021)

In spite of the fact that Learning Journals are optional, settings continue to produce them. There are a number of factors contributing to this practice:

In spite of the fact that Learning Journals are optional, and the collection of physical evidence is not a requirement, some settings still continue to choose to produce them. There are a number of factors contributing to this practice, but whatever the reason, the crucial thing to remember is that it is not necessary to record every single thing the child does. Practitioners must be balanced and proportionate in their approach, only recording observations that are useful or necessary. If they feel they are recording too much they probably are (see Top Tips blog).

Ofsted have often been cited as the force driving the production of paperwork. Inspectors have historically insisted on seeing written evidence of children’s progress. Each new recommendation appearing in a report is circulated on social media and rapidly adopted. This has been in spite of the clear directive in the EYFS for no unnecessary paperwork and insistence from Ofsted itself that it is not required.

The new Education Inspection Framework and accompanying Early Years Inspection Handbook (DfE, 2019) makes it very clear that inspectors must not ask for any documentation that is not an EYFS requirement. This means that inspectors should not ask to see learning journals or similar records.

Settings should never be producing learning journals just for Ofsted, however. If they choose to use them it must be because they benefit the child and the setting in their care for the child. If a practitioner feels that showing a learning journal to an inspector will be helpful, perhaps to illustrate a particular point about a child’s progress, then the inspector can be asked to look at it and accept it as supporting evidence.

Learning journals are a fabulous tool to facilitate information sharing about a child. They can include starting points from home, initial baseline assessments and ongoing progress reports, as well as ideas to support the child further. Whilst none of this HAS to be written down, in a busy setting, with many different practitioners observing a child, it can be useful to have a written record that all staff can refer to. It is even more helpful if a child attends more than one setting, or if there are concerns about their development, with outside agencies involved.

A childminder, working alone, may record very little as they have all they need to know stored in their memory. However, they may still choose to create a journal to share with others involved in a child’s care, to show Ofsted, to see patterns in a child’s development, or as a memoir of the child’s time with them. In all cases, no one’s recollection is perfect and so having some written cues can be helpful to act as prompts to jog the memory.

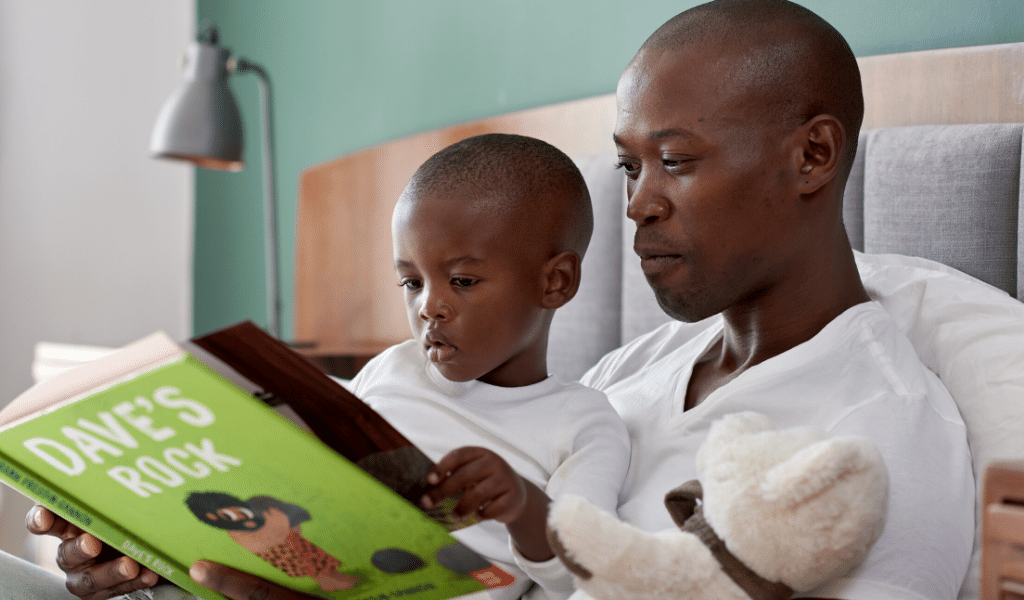

Learning journals are a wonderful way of involving parents in the setting. Fostering a sense of trust and partnership with parents has been particularly difficult during the Covid pandemic when many parents have been unable to go into their child’s settings and have reported feeling a sense of detachment as a result. Asking parents about their child, such as information about their home life, special people, ongoing progress and achievements, new interests etc. and including these in the learning journal shows that the parents’ knowledge and opinions are respected and valued. Sharing what the child is learning, their experiences, activities and the opportunities the child is engaging in whilst at the setting in the journal helps the parent to feel included and knowledgeable about their child’s time away from them, whilst at the setting. .

I care for a child whose mum contacted me during lockdown to say that her child had been reading her daily diaries and learning journal instead of a bedtime story each night. THAT is one of the reasons why I continue to produce learning journals. I love to see the joy on a child’s face when they look back through their journal and see a photograph of themselves, hearing the joyful animation in their voice when recounting the memory this has triggered. Children enjoy contributing, asking to add photos of their drawings or constructions. They really take ownership of their journals, eager to share these with their parents, who in turn are able to see that their child is happy, engaged and progressing.

In spite of often being moaned about, Learning Journals have remained popular and common practice. Practitioners are loath to give them up and perhaps with good reason. They do have many benefits as we have seen. So how to reduce the burden and give them new life?

Online journals arrived like a breath of fresh air: freeing practitioners from the reams of paper and mountains of glue sticks they had become slaves to, enabling them to spend more time interacting directly with children.

Online journals have all the benefits of paper journals and much more:

Until recently many online systems used the statements within Development Matters 2012 (Early Education, 2012) as an assessment tool in order to track children’s progress. Whilst practitioners may have found this helpful, it’s extremely important to remember that Development Matters was never intended to be used as a checklist – it said this on every page. The prevalence of such practice was one of the reasons why Julian Grenier completely repurposed Development Matters into what amounts to a completely new document, now styled as curriculum guidance, moving right away from assessment, other than the inclusion of a few observational checkpoints in the three prime areas.

It still provides examples of what practitioners might observe but these are to be used as a guide, alongside the practitioner’s existing knowledge of child development and professional judgement to determine what appropriate resources, activities and experiences they might offer. Development Matters then gives examples of ideas how practitioners might support children but again, these ideas are not intended to be identified as things a child must do or must achieve and so should not be used as literal ‘next steps’.

Following the changes, online platforms have taken varying approaches: some incorporating the new Development Matters; some including other new tools, such as Birth to Five Matters (Early Education, 2021); some also including the familiar 2012 Development Matters; some still adopting the ‘statement-ticking approach’; some a more appropriate ‘for reference only’ approach; and some removing all of these materials completely.

Practioners should approach with caution any system that still encourages the linking of individual progress statements from a tool such as Development Matters to observations, in the knowledge that the resultant tracking reports generated by an online journal system will be very limited in their scope, simply producing a broad, bland indication of the child’s direction of progress and not the whole picture of the child.

To avoid relying on the Development Matters or similar documents, practitioners should:

I use online journals in my own setting and would not consider returning to the paper method, having experienced the benefits of going online has afforded me. I will continue to create learning journals because I believe they are of value to me and the families who come to my setting.

When used appropriately, online learning journals are a powerful tool, that can benefit both practitioners and children. They are innovative, time-saving and effective in our increasingly digital society.